Spectacular Space Cities - Lets Talk Galaxies

From Galaxy Chocolate to Samsung Galaxy, the concept and name of a galaxy is nestled well within our society. Generally, people understand that it has something to do with space, but what they are exactly…well that’s anyone’s guess. Do they have anything at all to do with the chocolate? Do they all look the same and come in galaxy-print colours like pink, purple and blue? You’ll never know. Unless you keep reading…because that’s what I’m writing about.

The Great Debate

In the 1920s, astronomers went through a bit of a scuffle. “The great debate” took place, which questioned whether other “island universes” (now known as galaxies) existed beyond the Milky Way.

Astronomer Harlow Shapley insisted our home galaxy was the only one in the entire universe, and that any observed galaxies - considered to be clouds of gas - were just that. Herber Curtis disagreed completely; debating that observations of Andromeda, a galactic neighbor of ours, suggest that it may in fact be a galaxy separate and extremely far away from our own. At the heart of the debate was the question of the size of our universe - a concept which is difficult to comprehend even to this day. Could it really be large enough to house more than one huge galaxy?

Edwin Hubble (the Hubble space telescope’s namesake) was the one to end the debate in 1923. He measured the changing brightness of certain stars in the Andromeda galaxy, (bravely) did the math, and found that there was no way they could be in the Milky Way. They were just way too far away.

Like the Grinch’s heart, our universe grew three sizes that day (figuratively, of course) - enough to fit at least one more galaxy.

What’s a Galaxy?

A century later, we know a little more about our galactic neighbours.

I like to think of galaxies as little cities floating around in space. In which you’ve got suburbs, city centres and even some shady areas you wouldn’t want to end up in.

A galaxy is a collection of stars, gas, black holes, planets and star-forming regions all orbiting each other. A bevy of space stuff bunched together because gravity said so. Like the Earth orbits the Sun, all objects in a galaxy orbit a galactic centre - often inhabited by a supermassive black hole. The area closest to the monstrous black hole is like a bustling city centre. It is a hotspot in more than one sense; as superhot stars, neutron stars, white dwarfs and superheated gas rush around their short orbits. Then you’ve got the suburbs with stellar clusters, nebulae, star and planetary systems, and all types of stars. Cooler celestial objects tend to stay further from the centre of a galaxy, though they are often peppered about the galactic plane. Still, these areas can be bustling too! More drama happens in the suburbs than you’d expect. The same goes for the outskirts of a galaxy.

When it comes to where stars of a certain age or type can be found in a galaxy, it’s tough to say anything for certain as it always depends on how much of everything there is at the start. If there’s less cool gas in an area, you’ll find less young stars. If a region is riddled with dust, it will be tougher to accurately see what’s going on behind it. Astronomers also face cases like galactic mergers and unknown star-formation history, which puzzles them when they think they’ve finally worked out galactic maps.

Shapes and Colours

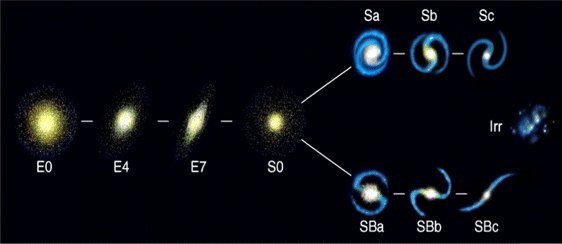

As far as we know, no two galaxies are exactly the same. The vast, expanding universe is covered in millions and millions of them. All in varying shapes, sizes and colours. In our human attempts to understand and organise things, a classification for all the different types of galaxies we’d observed was in the works. Hubble had a go at galactic classification; creating the Hubble tuning fork diagram. Aptly named after a musical tuning fork, not two guys named tuning and fork.

Noticing slight patterns in galactic shapes, he organised them into five categories:

Elliptical, E

In grades of ellipticity from 0 (very round) to 7 (very elliptical).

Abundant in our universe, elliptical galaxies are essentially giant ovals floating around in space. They’re huge, but pretty hard to spot because they can be relatively dim against their bright counterparts. Their dimness is caused by a lack of new star forming regions and a prominence of old stars which give off a lot of shy, red light. Because of this, astronomers theorize that maybe ellipticals are what all galaxies turn into at the end of their lives. Supporting such an idea, is the fact that they are often found in the midst of big galactic clusters, where they stand as possible remnants of galaxies colliding and eventually settling into one large, old mass.

Spiral, S, from a (compact spiral arms) to c (loosely wound spiral arms).

Barred spiral, SB, also judged by the tightness of their spiral arms but differentiated by a distinct bar-shaped centre where the arms come out.

The most well-known and stereo-typically “galaxy-looking” morphology, spiral galaxies aren’t too hard to identify. They’re what an AI gives you when you ask it to create an image of a galaxy.

Their spiral arms are denser areas of dust and gas, home to plenty of star formation regions, making them shine bright like interstellar highways. The reason some galaxies have arms is thought to be caused by the orbital shapes and speeds of stars being different around a galaxy’s centre. Thus, creating “density waves” where there’s more stars, gas, and dust in one area than another at a given time.

Spiral Galaxies are often younger than ellipticals, in the sense where we see new, hot star formation regions far more often in them. Why they have younger stars and spiral arms can be attributed to a bunch of reasons (like the density wave model), but one I find especially fun is the idea of a “recent” galactic merger having taken place. When two or more galaxies travel through the universe and gravitationally attract one another, they are bound to collide in a great, slow, spectacle of colour. As their dust and gas clouds collide, this creates environments perfect for new star formation.

Lenticular, S0, are the galaxies that are neither elliptical nor spiral but somewhere in between.

A largely misunderstood galactic type is that of the Lenticular galaxies. They confuse astronomers because while they have a bright central bulge and sometimes rings, they lack distinctive spiral arms coming from them. Often, lenticulars are tagged as in-between spiral and elliptical. Teenagers of galactic types, if you will.

Finally, Irregular galaxies, Irr, are thrown into the mix. Those are the ones which, you guessed it, don’t fit into any of the categories Hubble included in his tuning fork.

For a classification system created a century ago, the Hubble tuning fork diagram holds up pretty well for the average stargazer, as it gives a solid general overview of what a galaxy can look like. Still, as astronomers dug deeper into the universe with bigger and better telescopes, they realized that Hubble’s tuning fork needed some tuning itself.

Gérard de Vaucouleurs threw his hat in the ring 30 years later and tweaked Hubble’s creation to include more elaborate detail, like including a halfway kind-of-has-a-bar-if-you-squint section, SAB, for spiral galaxies. He also added a “d” to the spiral grade system, for galaxies with really faint and diffuse spiral arms, and r for those which had rings. Dwarf galaxies were added to the mix as well for the little ones. Basically, he loved playing spot the difference with plenty of Spiral and Irregular galaxies, and put it to work.

Milky Way City

Its easy classifying a galaxy when we have a head-on view of it. But when we can only see the side of a galaxy, things get tricky. As we can’t fly out and look at the Milky Way from above, our imaginations have to run free. And our math. Imagination and Math.

Our Milky Way

-

The name Milky Way comes from ancient Greece. As their night sky presented the ancient Greeks with this bright, white concentration of stars in the sky, it reminded them of milk. Terms for this white streak in the sky included “River of milk” or “Road made of milk”. Big on mythology at the time, the Greeks gave the origin of the Milky Way to be the spraying breast milk of goddess Hera, after she awoke to a baby Hercules nursing from her, per the orders of Zeus.

Our Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy around 100,000 light years in diameter. That’s 7.42 trillion Earths, if that helps in any way.

Four arms are identifiable, with two of them being particularly distinct, main character arms coming out from the bright, bar-shaped central bulge.

We’ve got a “thin disk” of young stars near and around the centre, and a “thick disk” of older stars spanning towards the edges of the plane. A “halo” orbits around the main galactic disk, with sparse stars and stellar clusters home to some of the oldest stars in the Milky Way.

Astronomers have been finding out a lot more about our galaxy recently, thanks to the Gaia Space Telescope. Its job since 2013 has been to create a 3D map of the Milky Way by scanning billions of stars. The equivalent of a census for the galaxy’s inhabitants. A brave feat, no doubt. Wouldn’t it be funny if we forgot to count ourselves?

Sagittarius A*

The Milky Way’s supermassive black hole, our city centre, is called Sagittarius A*. Surprisingly, it is found in the Sagittarius constellation. Unlike other celestial objects, black holes are notoriously hard to detect. The way Sagittarius A* and other supermassive black holes are spotted, is by their loudness. As astrophysicists poked around the Sagittarius A* region, they discovered an immense amount of radio waves coming from a “compact, non-thermal region”. Basically meaning, that they knew it couldn’t have been caused by just a bunch of superhot stars. So, concluding that there must be a black hole. The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics awardees pointed their instruments at our galactic centre and proved the existence of the Sagittarius A* by mapping the brightest stars orbiting the invisible spot. Now that they knew its exact address, more proof of Sag A* came in the form of a photo published in 2022. For those who’ve got to see it to believe it. Or rather, see the hot gas glowing around it, to believe it.

Our Neighbours

Housing around a 100 billion stars, every star you see when you look up at night is in the Milky Way. The closest star to us other than the Sun is Proxima Centauri, residing just four light years away. The brightest star in the sky, Sirius, is 8 light years away. Super close, in space terms. Black holes, neutron stars, supernovae, nebulae and other space stuff find their home in our city - making it anything but boring. Almost everything we know about space is thanks to all that’s around us in the Milky Way.

I’ll be sure to get into it all in the next blog posts!

-

The Milky Way is on a collision course with our nearest spiral galaxy, the one that started it all, Andromeda. In just 5 billion years, Andromeda will get a little too close for comfort and the night sky will change completely as our galaxies merge. You can imagine the chaos and majesty of it all. Its too bad I have plans that day, I would’ve loved to see it.

Conclusion:

The takeaway from all this is one, I’d say. Galaxies are so unfathomably large and complex and there’s just so, so many of them. And yet, our tiny human brains are still trying to figure them out.

They are pretty cool looking, to be fair.

-

It’s been a while, but I’m back! Noguum had been put on the back burner following a plethora of life developments and even some tech difficulties. Your questions kept coming in though, and this year your curious queries will be answered every month! Be sure to stay tuned! The universe only gets bigger by the minute.

Thanks to Jory for the topic suggestion!